China's River Rouge

One producer for one market. What could go wrong?

During the early nineteen-eighties I personally witnessed the beginnings of China’s rapid journey from cottage industry manufacturing and local marketing to the pinnacle of global manufacturing and industrial trade.

Early Chinese delegations visiting the United States seemed most focused on touring basic, vertical industries than observing finished goods or value-added operations. Over time, a distinct strategy for China’s development of global industrial capabilities became clear: control every facet of the basic industries and the value-added industries would take care of themselves.

Shifting the Center of Gravity

Large scale steelmaking in the United States did not begin until the 1870’s and even with the mercurial rise of Carnegie Brothers Steel in Pittsburgh, PA, American tonnage production would not surpass that of Great Britain until 1892.

British steelmaking methods were firmly entrenched and resistant to change leaving those methods as clear exemplars of procedural inefficiencies from which Alexander Holley would design the next generation of more efficient steelmaking facilities in the US. By the time the British realized they had lost global dominance in steel, the paradigm had shifted and the center of steelmaking gravity was in Pittsburgh.

Steelmaking methods are important but of equal importance is the reliable flow of raw materials into the process. Through a combination of investments, leases and stock purchases, the Carnegie brothers sought to control coking coal, limestone and iron ore needed to meet their production goals and provided a balance wheel against competition.

Enter River Rouge

Over a decade after Carnegie Steel was purchased by J. P. Morgan becoming United States Steel Corporation, automobile manufacturer Henry Ford approved a project for Ford Motor Company to realize his dream for having complete control of all facets and aspects of the manufacturing process.

Coal mines, iron ore reserves, glass factories, rubber plantations, hardwood forests, and others, were purchased foregoing the need for any middlemen who could exert influence upon the company through material cost uncertainty or availability. Had Ford stopped at this point he could have realized his dream and saved Ford shareholders a great deal of money.

A large undeveloped tract of land along the River Rouge near Dearborn, Michigan, ostensibly purchased to serve as a private bird sanctuary to the Ford family, became one of the largest construction sites in Michigan which would replace bird nests with Basic Oxygen Furnaces for making the steel for automobiles. Also included in The Rouge was glassmaking, coking coal production, steam and electrical power production, woodshops for making wooden wheel spokes and expansion plans to build a tire factory for Ford cars alone.

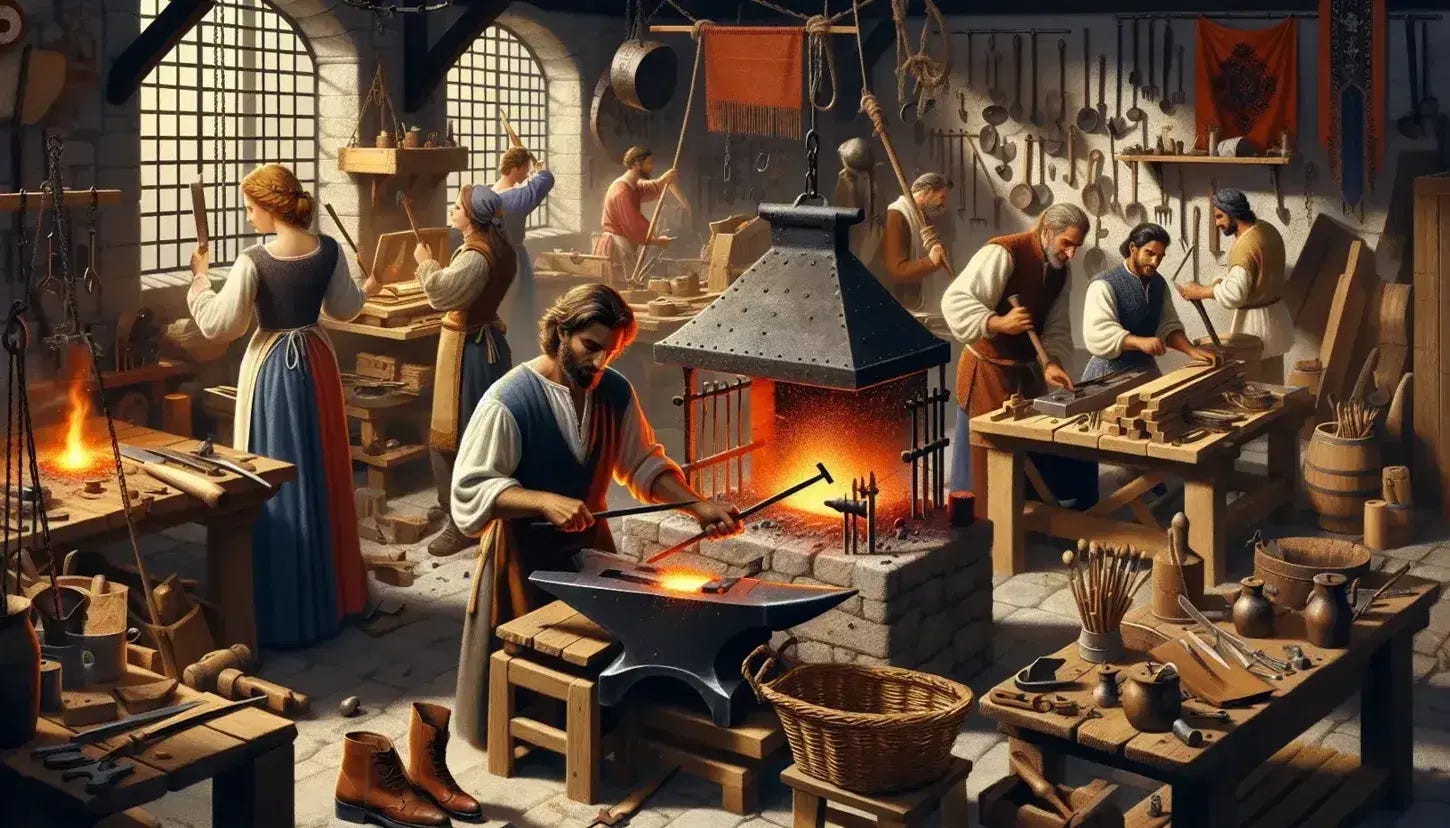

Contemporary critics of the scope and scale of The Rouge project were abundant, not the least of which was William C. “Billy” Durant, the founder of General Motors Corporation, a strong advocate of distributed manufacturing and one not hesitant to refer to The Rouge as a glorified medieval guild.

While a large, vertically-integrated manufacturing facility can offer economies of scale for a single product with a long design lifecycle, vertical integration is not responsive to the real world of design pivots and changes in market requirements. Guilds move far too slowly.

Distinct Strategy/No Strategy

China’s distinct strategy has held fast for almost forty years and we now see the most economically important resources for meeting the demands of the global markets being controlled by Beijing. The Chinese chose to follow the lead of Henry Ford and control the resources whether they existed in-country or ex patria yet they chose to follow Billy Durant’s distributed manufacturing model which constructed smaller capacity factories in greater numbers which are responsive to the marketing dynamics, known or unknown.

Over the same period of time, the US has operated with no apparent consistent strategy for meeting global market requirements since we see ourselves as the only market to be served and China as the only producer who can fulfill that need.

We may awaken soon to discover that service economies are difficult to maintain.